- Overstory

- Posts

- Unwanted Guests: Lanternflies and the Tree of Hell

Unwanted Guests: Lanternflies and the Tree of Hell

A two-for-one special of invasive species spreading up the East Coast

My old apartment in Chelsea opened up to a courtyard in the back. There was a massive tree in that courtyard which was a welcome respite from the urban landscape. Having that green outdoor space at my apartment actually did a lot for me– sunlight and greenery was a stark contrast from my prior apartment which felt more like a dungeon.

When I first moved in, I was just starting to learn more about tree identification. I spent a good amount of time going back and forth on what kind of tree I had behind my apartment. It had pinnate leaves (meaning multiple leaflets were lined up on a central stalk). That helped me narrow it down to a few options I found on the internet– black locust, ash, walnut. All native trees to the East Coast. Thinking about it got me excited. After 2 years of living in a light-deprived shoe box, I had an apartment with an outdoor space and a huge, old tree in the back.

I made the most out of this outdoor space. I strung up lights, got a grill, some outdoor furniture. I also enjoyed the view of the canopy of my new tree.

As the clumps of spinners started falling in the late summer, I got a closer look and couldn’t match them to any of the trees on my list. After a little bit of googling, my answer became clear… and it was quite disappointing. It was a Tree of Heaven.

While the name may sound great, the Tree of Heaven (“TOH”) is one of the most invasive plant species in the U.S. It is native to China, and was brought to Europe and the U.S. during the 1780s. A hundred years later, people began to realize they couldn’t control the spread. The TOH was taking over and displacing our native tree species.

One way the Tree of Heaven does this is by growing quicker than any of the native trees around it. The TOH grows 3-6 feet per year. That is 2-3x the rate of most native tree species (including white oaks, elms, and maples). That rapid growth rate means that TOHs get the first sunlight as saplings and shade out competing native trees.

Just as the tree grows quickly above ground, its roots grow quickly underground. Like bamboo, new saplings will shoot up from its root system. So when you see one, look around, because there are likely more. In fact, if you cut down a Tree of Heaven its root system will shoot up dozens of new saplings in the area around where the original fell.

As if it couldn’t get worse, those vast root networks also exude chemicals that inhibit the growth of other trees.

I was so disturbed reading this that at the time, I actually reported it and awaited a phone call from NYC Parks to tell me they were coming to remove it. I can’t help but laugh thinking about how naive I was.

Turns out there was a TOH behind that apartment. There is a TOH behind my girlfriend’s apartment. There is also a TOH behind my new apartment in the East Village. And from my rooftop, I can see the tops of trees in courtyards all around me… all Trees of Heaven. I drive down the highway now and I can’t help but notice them on the side of the road. Turns out they don’t mind road salt. Trust me when I tell you, these trees are everywhere.

The above picture shows the High Line before it was converted to a park. The abandoned area was covered with Trees of Heaven (see the pinnate leaves in the center).

A Familiar Friend

Our native ecosystems took tens of thousands of years to develop. There is an intricacy in the way that parts of an ecosystem interact that constantly amazes me. Certain insects and animals rely on certain plants who rely on other insects and animals and it all fits together like an intricate puzzle.

The Tree of Heaven doesn’t fit in that puzzle. As a transplant in our ecosystem, it actually hosts very few other plants or animals. That at least was the case until 2014, when a Spotted Lanternfly was discovered in Pennsylvania.

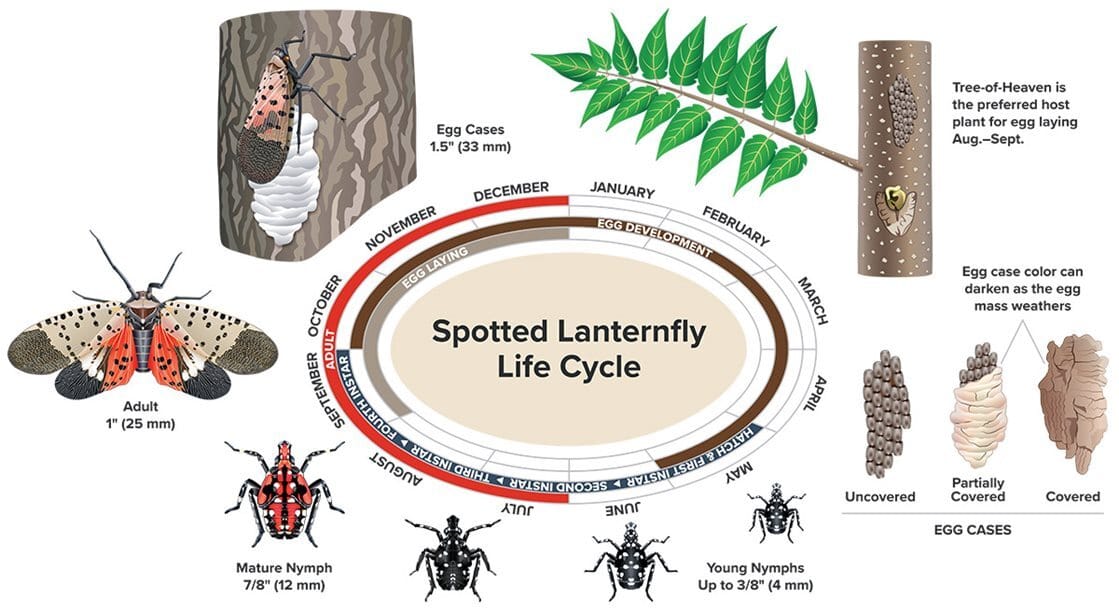

The Spotted Lanternfly, also from Asia, found its home-away-from-home in the abundant Trees of Heaven across the East Coast. Beginning in Pennsylvania, the Spotted Lanternfly has spread rapidly and in 2020 reached New York. At this point, 5-years later, these flies are everywhere in New York. When early summer rolled around at my old apartment, I could walk outside and find 10 at any moment (read “find” as “kill”).

Lanternflies are pervasive sap consumers. They target 70+ native plant species, greatly inhibiting the growth of those plants and limiting the access to native insects. They also excrete a sugary substance on surfaces, promoting the growth of a sooty black mold. These lanternflies are wreaking havoc on our ecosystems and they are growing fast.

In Asia, their natural habitat, there are natural predators that keep them in check, but here they have no natural predators. For now, the solution is fairly rudimentary– if you see one (or more importantly their egg masses) kill it.

When the spring rolled around at my old apartment, I started seeing these young nymphs everywhere.

The Spotted Lanternfly has actually gotten a lot of attention. I think news organizations have covered it well and many people are aware that this is an invasive species. In large part that is because of how recent and dramatic their introduction was.

What I don’t think people appreciate (at least I didn’t) is the layer beneath the spotted lanternfly— their host, the Tree of Heaven.

The way that two invasive species interact together is truly interesting (and daunting).

While we don’t have a solution yet, knowledge is power, and recognizing things like this make for a compelling argument as to why we should value native plant species. I’ll let scientists much smarter than I find the long-term solution, but in the meantime, I plan to drive myself crazy spotting Trees of Heaven and showing lanternflies the weight of my shoes.

Reply